coop_sql_notebooks

Combining Data in SQL Crash Course - How to use JOIN and UNION

By: Martin Arroyo

Estimated Reading Time: 26 minutes

Table of Contents:

- What are joins and why do we use them?

INNER JOIN- Working together through an example of the most common join- INNER JOIN

vsLEFT JOIN` - Caveats & Using them in Practice -

Comprehension Check - Using Joins in Practice:

INNERandLEFTJoins - Final Comprehension Check - Combining Data Using

JOINandUNION

Introduction: Combining Data - Joins and multiple tables

Welcome to the Combining Data in SQL Crash Course - How to use JOIN and UNION! In SQL 101 - Introduction to Databases and Querying, you learned how to write queries that selected, filtered, aggregated, and ordered data from a single table. In this class, we are going to add to your SQL toolbox by teaching you how to combine data from multiple tables to generate deeper insights. You will also learn more advanced querying techniques, such as using more advanced functions, subqueries, and more!

In this crash course, we will cover what you should know about joins and unions in SQL. Understanding how to combine data from multiple tables is crucial to being able to work with data in a database, since you will mostly be dealing with more than just one table. Joins are also one of the most common technical interview topics that you will encounter, so they are definitely something you should work on!

We will walk you through what joins and unions are and why we use them in this section. Then, in the following SQL 102 notebook, you will have plenty of practice writing your own queries to combine data. By the time you’re finished, you’ll know enough to nail any questions on joins in your next technical interview!

What are joins and why do we use them?

Note: It may be useful to open SQL 101 alongside this reading to go over some of the examples and concepts

Databases generally have more than one table. And since databases store tables that are (generally) related to one another, we need a way to combine data from multiple tables. We’re going to use our fictional restaurant database from SQL 101 as an example. You may recall that there is a Customers table which keeps track of our customer demographic information. There is also a Reservations table, which keeps tracks of reservations made by customers. If we want to answer a question like, “What are the top 5 states that our all-time most frequent customers come from?”, then we need to combine the data from those two tables.

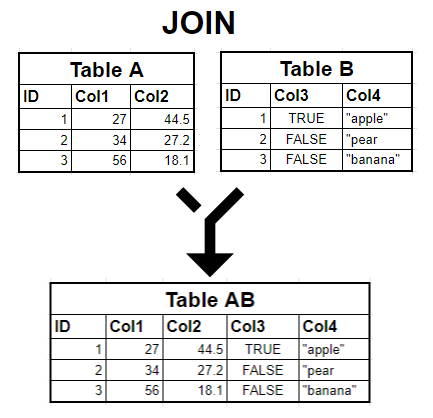

When we join data, we are combining two or more related tables into a single view to add context to our data to generate more holistic insights. We use common attributes (or columns) to establish relationships between the tables, along with constraints that control how records (or rows) are matched between them. In SQL 101, we mentioned that these relationships are often (but not always) established using primary keys and foreign keys. The direction that we combine data in is from left to right, or horizontally, so our tables usually get wider since we add more columns. Joins say, “Combine this data from left to right.”

There are four fundamental join types that you should know about in SQL - INNER, LEFT, RIGHT, and FULL OUTER joins. Each join type provides slightly different results, and you select the type to use based on what your analysis calls for. Other join types that you should be aware of are the CROSS, SELF, and NATURAL joins. We will not cover these last three types explicitly, but we encourage you to read about them on your own time.

What are unions and why do we use them?

Along with joins, another operation that is used to combine data are unions. But what exactly are unions?

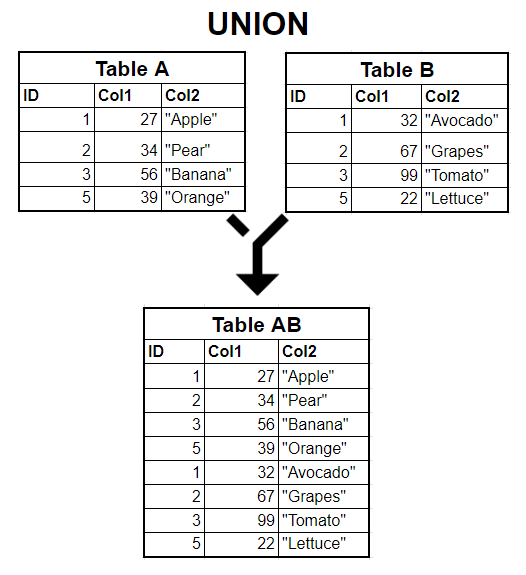

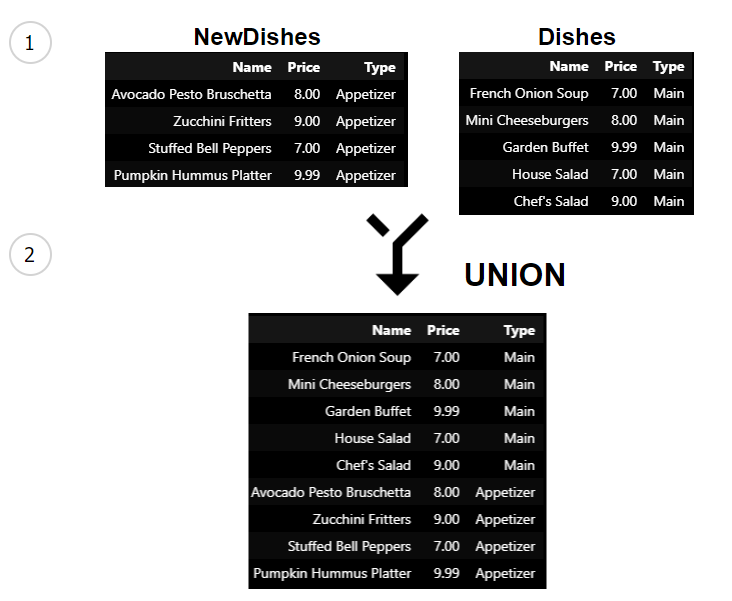

When we join data, we are typically combining two tables together horizontally, meaning that when we join the data our result set gets wider because we’re adding more columns. Unions, on the other hand, let us combine two tables together vertically - they say, “Combine this data from top to bottom.” In other words, joins combine tables to add more columns to our data while unions combine tables to add more rows.

Both unions and joins can be used to add more context to your data. Unions are best to use when you have data from two very similar tables that can be combined into a single view. Using our fictional restaurant again as an example, there is a Dishes table that has the main menu items and a NewDishes table which has dishes that are NOT in the menu yet. We can use UNION to show us all the current and new dishes together instead of in separate tables. This will let us get a more holistic view of the restaurant’s offerings.

We will revisit this example and walk you through a UNION query in the Practical Union Scenario section below.

Comprehension Check - Join and Union Basics

Answer the questions below to check your understanding of what we have covered so far. Try to answer the questions first before looking at the answers:

1. Why is understanding joins crucial for working with databases?

Click to reveal the answer

Understanding joins is crucial because databases generally have more than one table and joins allow us to combine data from these tables to generate deeper insights.

2. What are the four fundamental join types discussed?

Click to reveal the answer

The four fundamental join types discussed are INNER, LEFT, RIGHT, and FULL OUTER joins.

3. In what direction does a join combine data?

Click to reveal the answer

Joins combine data from left to right, or horizontally.

4. How do unions differ from joins in terms of the direction of data combination?

Click to reveal the answer

Unlike joins that combine tables horizontally, unions combine tables vertically.

A hypothetical join scenario

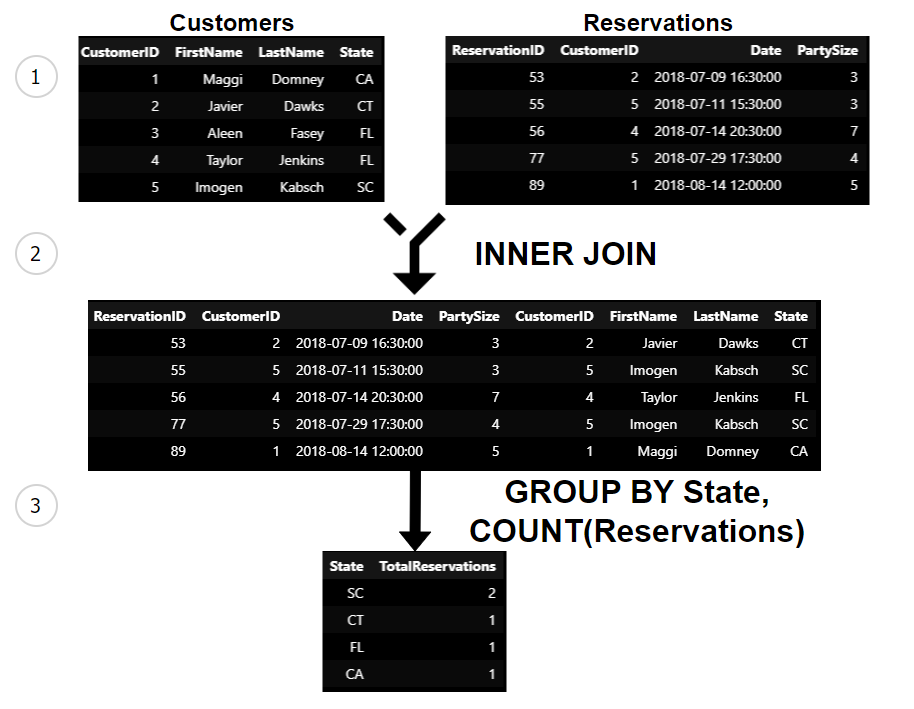

Let’s return to our hypothetical join scenario: using the Customers and Reservations table from our restaurant database to answer, “What are the top 5 states that our all-time most frequent customers come from?” How would we do this?

To do this, we would join the customer and order tables together using a common field (or fields) that establishes a relationship between them. In relational databases, this is usually done using a primary key/foreign key relationship. This is not always the case - it’s possible to join fields that don’t have an established Primary Key/Foreign Key relationship - but it’s one of the most common. If there isn’t a primary/foreign key relationship, you can use any columns that have matching data types and values.

Next, we would create some constraint that determines which rows from the Customers table should be matched with what rows in the Reservations table in our query result. Usually our constraint would say something like, </em>“Give me all the rows where the value in the column from this table is the same as the value in the column from that table.”</em>

Example Constraint:

Orders.customer_id = Customers.id

The query for this example would look like:

SELECT C.State, COUNT(R.ReservationID) AS TotalReservations -- We are counting the number of reservations by each state

FROM Reservations AS R -- The 'Reservations' table is on the "left-side" of the join. We give it an alias of 'R'

INNER JOIN Customers AS C -- The 'Customers' table is on the "right-side" of the join. We give it an alias of 'C'

ON R.CustomerID=C.CustomerID -- This is our constraint saying "Only give me the rows where the customer id in 'Orders' matches the id in 'Customers'"

GROUP BY C.State -- We're summarizing our results by what state our customers are from

ORDER BY total_reservations DESC -- Since we want to know which states have the most reservations, we order the counts from greatest to least

LIMIT 5 -- We only want to see the 5 states with the most reservations, so we limit our results to the first 5 rows

This is slightly more complex query than what you may be used to writing coming from SQL 101, but we will break this down line-by-line a little later on.

First, we’ll introduce you to the basics of joins using simpler examples. Then we’ll come return to this more “real world” example and break down how it works.

Extra Context: Code Comments

You may have noticed that we used “

--” followed by some text in the query above. These lines of text are called “comments”, which are notes in the code written by the developer to communicate what a particular line or section of code means. All coding languages have a way for developers to leave these comments in their code so that they can let future readers understand their thought process and why something was done.We use a comment symbol to let the computer know that “this is not code, so don’t execute it!” Each programming language will have its own symbol for comments. In SQL, it is most common to use “

--” for a single-line comment. Check the documentation for the SQL dialect you are using to be sure, though!

INNER JOIN - Working together through an example of the most common join

Joins can be a difficult topic, so we’ll practice doing some together and explain everything that is happening as we go along.

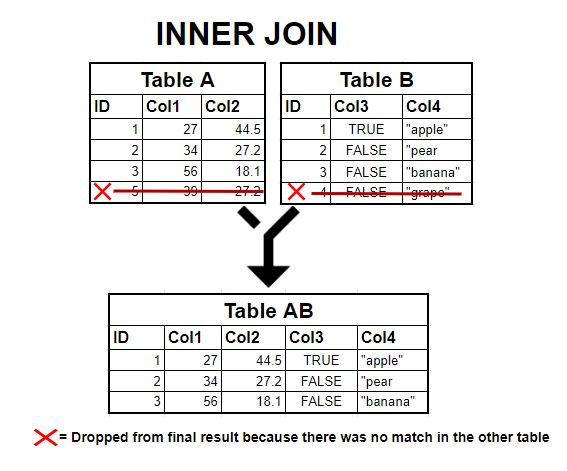

The first type of join we’ll work on is the INNER JOIN. This is the most common join that we will use.

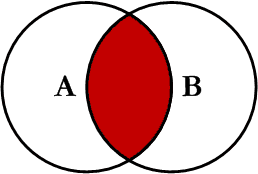

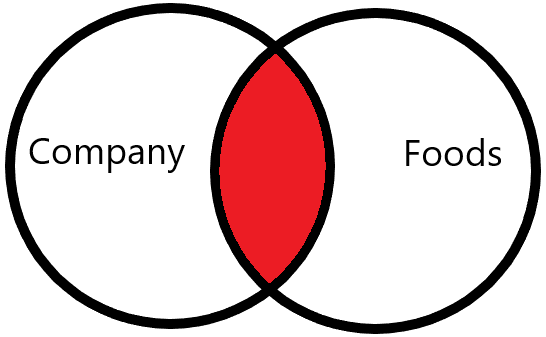

When we use an INNER JOIN, we are saying that we only want the rows from both tables that match constraints that we set.

Let’s assume that we have two tables - A and B - that we want to join together, only including the rows that are common to both of them.

Here is what that query would look like:

SELECT *

FROM A -- This is the table on the "left-side" of the join

-- Specifying the join type

INNER JOIN B -- This is the table on the "right-side" of the join

-- Specifying the join column (`column1`) and constraint (`=`)

ON A.ID=B.ID

This is a visual representation of which rows will be returned between the two tables after the join:

What gets matched between the two tables

As you can see, we’re keeping only the rows between the two tables that match based on our join columns and constraints. These query results will only include the rows that match our constraints while dropping the rest of the rows that don’t match.

Pro-Tip: You don’t need to specify the

INNERfor theINNER JOIN- you can simply useJOIN. However, it is good practice to be explicit when writing queries, so you are encouraged to use theINNERkeyword whenever you mean an inner join.

Join Syntax

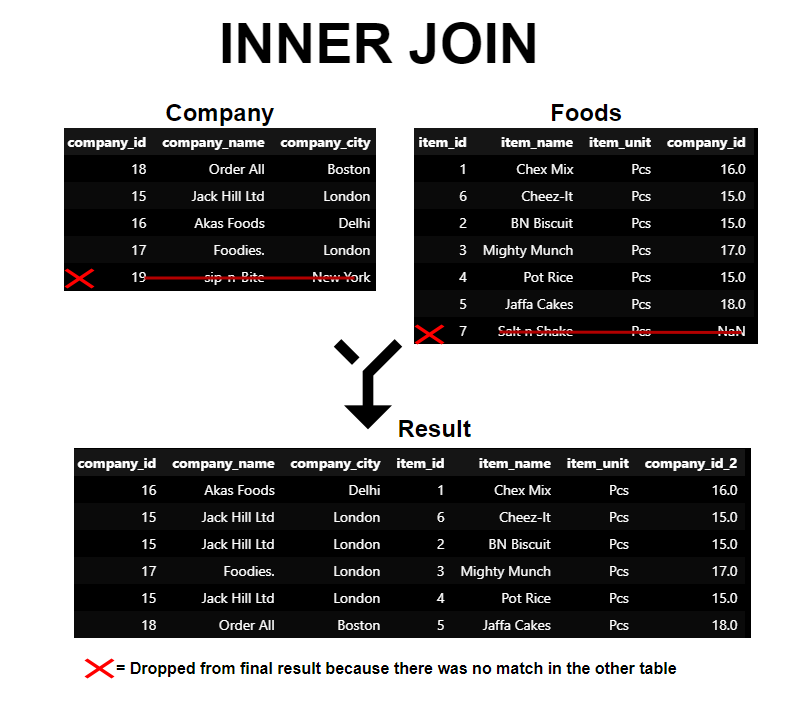

We’re going to use two tables from another fictitious database for the following examples - Company and Foods. The Company table has information about different foods companies, and Foods has information about food products sold by the companies in Company. They have a primary key/foreign key relationship using the company_id column found in each table. Our goal is to simply join the two tables together to see the company information associated with each food product.

Writing Join Queries

When we write joins, we always specify the join type, column(s), and constraint(s) together. Joins come after the FROM clause and before the WHERE and GROUP BY clauses in our queries.

To specify the type of join we want to use, here is the general form:

{Join Type} {name of table to join}

Example: INNER JOIN Foods

To specify the column and constraint, we use the following form:

{First Table.Column to join on} {constraint} {Second Table.Column to join on}

Example: Company.company_id=Foods.company_id

Putting it all together, writing the join would look like:

INNER JOIN Foods

ON Company.company_id=Foods.company_id

Extra Context: Dot Notation in Queries

We typically use dot (

.) notation when we join two or more tables in SQL. This is so that we don’t confuse the RDBMS when two tables have columns with the same name.Here’s the general syntax:

table_name.column_name

Now let’s put the whole query together now and see the how it all works:

SELECT *

FROM Company

INNER JOIN Foods

ON Company.company_id=Foods.company_id

As you can see, one row in each of the tables gets dropped from the final result. This happened because the value for company_id in these rows did not exist in both tables. Only the rows where the value for company_id exists in both tables are included since that is how they are matched.

LEFT JOIN

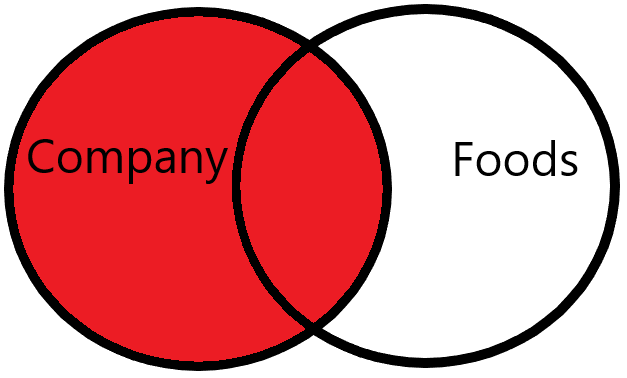

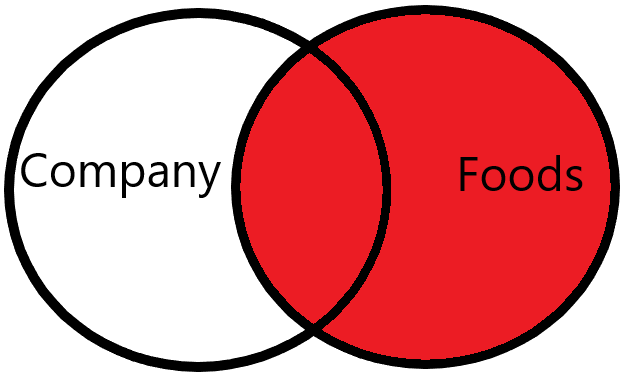

A LEFT JOIN is the other most common join after INNER JOIN. The difference between the two is how the rows are matched in the query result. While an INNER JOIN includes only the rows that match from both tables, a LEFT JOIN will keep all the rows from the left-side of the join and only those that match from the right-side. When this happens, instead of dropping those rows like the INNER JOIN, any values in unmatched rows are set to NULL. Visually, the matched rows will look like this:

If you’re new to LEFT JOIN, you’re probably wondering what was meant before by “left-side of the join.” Visually, we can see that there is a table on the left side that has all of the rows included with only the rows at the intersection included from the right. But how does that translate to an actual query?

SELECT *

FROM Company -- This is the table on the "left-side" of the join

LEFT JOIN Foods -- This table is on the "right-side" of the join

ON Company.company_id=Foods.company_id

Simply put, the table on the “left” of a join type is the one used in the FROM clause and the table on the “right” is the one specified after the join type (LEFT JOIN in this case.) Columns and constraints otherwise work the same as the INNER JOIN. The syntax is virtually identical between the two joins, but it’s important to know how they work and the caveats for all join types.

INNER JOIN vs LEFT JOIN - Caveats & Using them in Practice

Caveats

Looking at the result of the two queries, you should notice that the LEFT JOIN query gave you an extra record that was missing from the INNER JOIN query. The sip-n-Bite company is missing from our first query. Why?

Well, we know that we joined the two tables together based on matching company_id. We also know that INNER JOIN only keeps rows from both tables that match. Since we know that the record exists in the company table, that must mean that there is no record for the sip-n-Bite company in the foods table. You can confirm this by looking at the foods table and querying for company_id=19, which will return no result since it doesn’t exist.

When do I use one over the other?

Whether to use an INNER JOIN or a LEFT JOIN is something you must consider for your particular use case. Do you only want to consider the rows that match between your tables? Then choose an INNER JOIN. Want to make sure that rows are kept from the left side of the join? Then - you guessed it - use a LEFT JOIN.

Practical Usage

By and large, the majority of your joins in practice will either be an INNER JOIN or a LEFT JOIN. It is worth it to learn them well and become really comfortable with using them, as well as knowing when to use them. The other joins mentioned are not used as much in practice, but it’s good to know about them - especially for technical interviews!

Comprehension Check - Using Joins in Practice: INNER and LEFT Joins

Answer the questions below to check your understanding of what we have covered so far. Try to answer the questions first before looking at the answers:

1. What does an INNER JOIN do in SQL?

Click to reveal the answer

An `INNER JOIN` in SQL returns only the rows from both tables that match the specified constraints.

2. Is it necessary to specify the INNER keyword when performing an inner join?

Click to reveal the answer

It's not strictly necessary to specify the `INNER` keyword; you can simply use `JOIN`. However, it is good practice to be explicit.

3. How do you specify the columns and constraints for joining two tables?

Click to reveal the answer

To specify the columns and constraints, we use the `ON` keyword followed by {First Table.Column to join on} {constraint} {Second Table.Column to join on}, such as `ON Company.company_id=Foods.company_id`.

4. What is the primary difference between an INNER JOIN and a LEFT JOIN?

Click to reveal the answer

An INNER JOIN returns only the rows that match from both tables, while a LEFT JOIN returns all the rows from the left-side table and only the matching rows from the right-side table. Unmatched rows from the right-side table will have NULL values.

5. How can you tell which table is on the “left-side” of the join and which is on the “right-side”?

Click to reveal the answer

The table that comes after the `FROM` clause in your query is the "left-side" table; the table that comes after the `JOIN` type is the "right-side"

A Walkthrough of a Practical JOIN Example

Scenario

Remember our hypothetical join scenario and the complex query we wrote from earlier? Now that you have some more exposure to joins, let’s revisit this query line-by-line. First, let’s reiterate the question and the query:

Question: “What are the top 5 states that our most frequent customers come from?”

Example of JOIN query

Query:

SELECT C.State, COUNT(R.ReservationID) AS total_reservations -- We are counting the number of reservations by each state

FROM Reservations AS R -- The 'Reservations' table is on the "left-side" of the join. We give it an alias of 'R'

INNER JOIN Customers AS C -- The 'Customers' table is on the "right-side" of the join. We give it an alias of 'C'

ON R.CustomerID=C.CustomerID -- This is our constraint saying "Only give me the rows where the customer id in 'Orders' matches the id in 'Customers'"

GROUP BY C.State -- We're summarizing our results by what state our customers are from

ORDER BY total_reservations DESC -- Since we want to know which states have the most reservations, we order the counts from greatest to least

LIMIT 5 -- We only want to see the 5 states with the most reservations, so we limit our results to the first 5 rows

Breakdown of JOIN query

Here is a visual breakdown of how the query is being executed and what’s happening:

Now that we can see what’s happening to each table, let’s step through each line of the query together and break down how it all works:

SELECT C.State, COUNT(R.ReservationID) AS total_reservations

We’re selecting the State column from the Customers table and counting the total number of reservations from the Reservations table for each state. We have created aliases for each table - C for Customers and R for Reservations. This is common practice when we write join queries. If two tables have columns with the same name, SQL needs a way to understand which table and columns you are referring to in your query. This is why we use C.State, which is using the State column from the Customers table.

FROM Reservations AS R

Here we started with the Reservations table, and we gave it an alias, R. This will allow us to refer to the table using R instead of the full name; it’s simply a shortcut for us so we don’t need to use the full name of the table each time we reference it. We say the Reservations is on the “left-side” of the join since it is in the FROM clause.

INNER JOIN Customers AS C

This is where we indicate the type of join we want and our intent to join the Customers table. We have specified an INNER join as the type of join that we want to use. We gave the Customers table an alias of C to make it easier to reference.

ON R.CustomerID=C.CustomerID

Our constraint is specified on this line. Here, our constraint says, “Only match the rows between the two tables that have matching customer IDs.” Or in other words, “make sure the reservations are associated with the correct customer using their ID number.”

GROUP BY C.State

We want to know the total number of reservations by state, so that’s the column we use in our GROUP BY.

ORDER BY total_reservations DESC

LIMIT 5

Here, since the question asks us to only show the top 5 states in our results, we:

- Use the

ORDER BYclause to first sort our results by the number of total reservations, from greatest to least. - Since we only want the top 5, we use

LIMIT 5to restrict the results to just the first 5 rows

This was a complex query that answered a very practical question for our restaurant! It demonstrates how we can combine the querying concepts that we have learned so far to answer more and more sophisticated questions from the data.

Also, consider the fact that you would not be able to answer this question using either Customers or Reservations alone. It was only after combining them that you were able to get deeper insights. That’s a large part of why joins are useful and often necessary.

Recap on JOIN queries

Let’s sum up what we’ve covered so far for joins:

- Joins allow us to combine data horizontally by adding new columns from other tables

- There are four fundamental types we should know:

INNER,LEFT,RIGHT, andFULL OUTER - Each type has slightly different rules for what rows will be included in the query results

INNER JOINkeeps only the rows that are matched between the two tables in the final resultLEFT JOINkeeps everything from the “left-side” of the join and only includes rows from the “right-side” that have a match; Rows that aren’t matched to the “left-side” are filled with NULL valuesINNERandLEFTjoin are the two most common query types in practice - know them well!

Now we’ll continue on to the other two fundamental joins you should know: RIGHT and FULL OUTER joins.

RIGHT JOIN

As mentioned earlier, RIGHT JOIN is rarely used in practice. This is because you can do the same thing using just a LEFT JOIN, so there aren’t many (if any) use cases where you would want to exclusively use it. However, it is a join type to be aware of and is commonly asked about in interviews, so let’s cover it.

The opposite of the LEFT JOIN, RIGHT JOIN includes all the rows from the “right-side” of the join and only rows that match from the “left-side”. Also, similar to LEFT JOIN, values in rows from the other side of the join that don’t match are set to null and included in our query results. Visually, the resulting matches look like this:

Here is the query breakdown:

SELECT *

FROM Company -- This is the table on the "left-side" of the join

RIGHT JOIN Foods -- This table is on the "right-side" of the join

ON Foods.company_id=Company.company_id

Syntactically, it is almost identical to the other joins. Let’s run a RIGHT JOIN query and see the results.

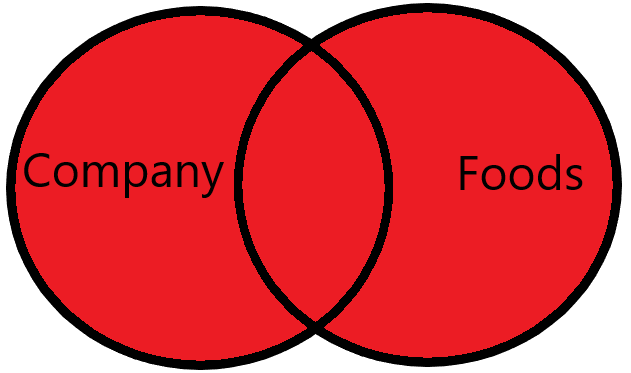

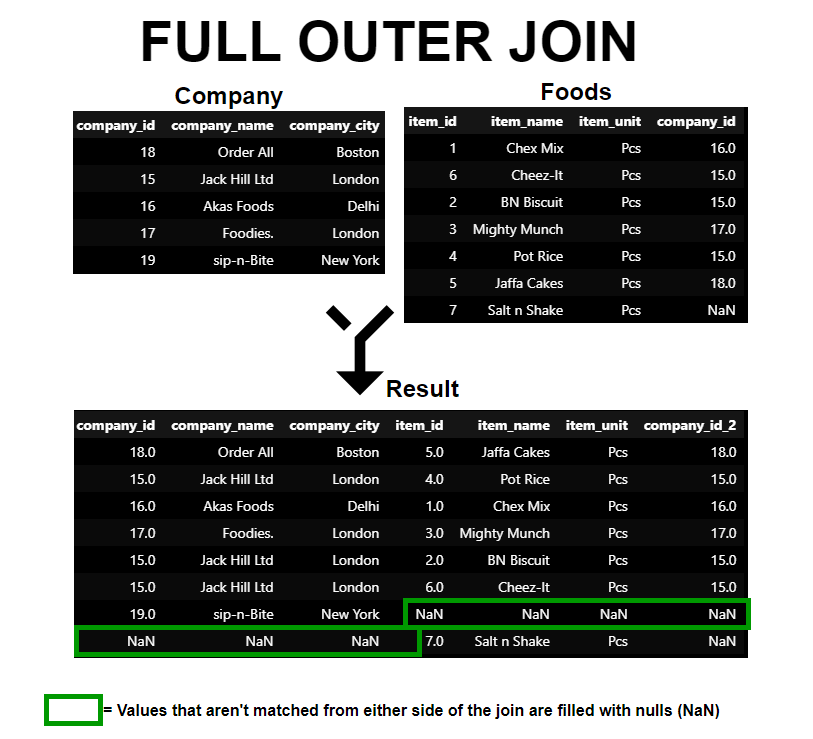

FULL OUTER JOIN

FULL OUTER JOIN is another join type that isn’t used as often as left or inner joins in practice, but it is much more common than the RIGHT JOIN. We use FULL OUTER JOIN when we want to include all the rows from both sides of the join, showing the rows that match between the two and otherwise giving null values where there isn’t a match between the tables. A FULL OUTER JOIN is like a combination of both the left and right join types.

Here is how the matching looks visually:

The query syntax is pretty much identical to the others, aside from specifying the join type itself:

SELECT *

FROM Company

FULL OUTER JOIN Foods

ON Company.company_id=Foods.food_id

Practical considerations for selecting columns for joins

Joining datasets usually depends on primary and foreign key relationships, but these relationships may not always be clear (or available.) You may find yourself in a situation like this when dealing with a new data set. In these cases, understanding the data’s origin, purpose, and contents can help. This can be done by finding documentation like data dictionaries or entity relationship diagrams (ERDs) or consulting with subject matter experts.

If there’s no documentation and no experts are available, exploratory data analysis becomes crucial. This involves understanding column data types, summary statistics, and identifying missing values. Look for unique identifier columns, or possible primary keys - the values in these columns should be unique and non-null. The information_schema, found in most relational databases, may also provide helpful metadata that can point to relationships.

To sum things up, you should always attempt to find any documentation available for the data you are using in order to understand how you can connect tables together. Additionally, seek out help from subject matter experts who know the data well. If you can find neither of these sources for a data set you are working with, then exploratory data analysis becomes crucial. You will need to develop an understanding of the data to help you pick out the columns that can be used to join the tables together for your analysis.

A Walkthrough of a Practical UNION Example

Scenario

Let’s walk through a practical scenario where we can use UNION to help us combine data. There are two tables in our database that hold information our restaurant’s menu items - Dishes and NewDishes. Dishes holds data about the items that are currently on our menu; NewDishes has data about items that are not on the menu yet, but could be.

The restaurant owners tell us that they are planning on making some changes to the menu next month. They want to replace all of the appetizers in the current menu with new ones from the NewDishes table.

UNION query example

To help the restaurant create their new menu, we’ll write a query that combines only the appetizers from NewDishes and all of the dishes other than appetizers from Dishes:

-- The first query that gets the appetizers from NewDishes

SELECT Name, Price, Type -- We are selecting just the name, price, and type of the dish. For UNION queries, the columns you select and their order matter

FROM NewDishes

WHERE Type='Appetizer' -- We are filtering for just the appetizers from NewDishes

UNION -- Here we using the UNION keyword to say "Create a UNION between the top query and the query immediately following

-- This is the second query that gets all the dishes other than appetizers from Dishes

SELECT Name, Price, Type -- Again, selecting the same columns that we did for the first query and in the same order - THIS IS IMPORTANT!

FROM Dishes

WHERE Type<>'Appetizer' -- Filtering for all dishes other than Appetizers

Output (first 5 rows only):

| Name | Price | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Avocado Pesto Bruschetta | 8.00 | Appetizer |

| Zucchini Fritters | 9.00 | Appetizer |

| Stuffed Bell Peppers | 7.00 | Appetizer |

| Pumpkin Hummus Platter | 9.99 | Appetizer |

| French Onion Soup | 7.00 | Main |

Breakdown - UNION query

Here’s a visual representation of how this query works:

Let’s break down what’s happening in here step-by-step:

First, you might notice that we’re actually using two separate queries. This is exactly how we write UNION queries - by combining the results of two queries on top of each other. We’ll start with the first part:

SELECT Name, Price, Type

FROM NewDishes

WHERE Type='Appetizer'

We’ll call this part of the query the “top query.” It is simply a SELECT query on a single table with a filter. We are querying the NewDishes table and filtering for only the Appetizer dishes.

It’s important to note both the columns that are being selected and their order - these are critical to UNION queries. For the results of both the top and bottom queries to align, the columns you select must have the same data type and be in the same order in both queries. You’ll see that we use columns with the same data type and in the same order for the “bottom query.”

Also, each query (both top and bottom) must select the same number of columns as well. You can’t have one query select five columns and the other select four - that is an error.

UNION

Here is our new clause - UNION. By including UNION after our “top query”, we are saying, “Combine the results from the query on top with the results from the query on the bottom”

Another important distinction to make here is that by saying UNION, we are also telling SQL that we don’t want duplicate values in our final query result. If we instead didn’t need to remove duplicates, we could use UNION ALL instead, which leaves in the duplicate rows between the top and bottom query.

Pro-Tip: While using just

UNIONis handy when we don’t want duplicate rows in our results, it can cause performance issues when we are working with larger data sets. It is similar to theDISTINCToperation and should be used sparingly. If performance becomes an issue (e.g. query takes too long to run), switch to usingUNION ALL- you’ll get duplicate rows but your query will run faster. Whether or not to make the tradeoff on performance vs. convenience is a judgement call you will have to make depending on your situation.

SELECT Name, Price, Type

FROM Dishes

WHERE Type<>'Appetizer'

We’ll call this part the “bottom query”. In it, we’re saying, “Give me all the dishes in the Dishes table that aren’t appetizers” since we want to replace the current appetizers with the ones found in NewDishes. Again, we select columns that match both the data type and order of the columns from the “top query”.

Recap on UNION query

To sum everything on UNION queries up so far:

UNIONqueries allow us to combine data vertically instead of horizontally (like joins)- To write

UNIONqueries, we combine the results of two queries using theUNIONclause - The two queries must follow these rules:

- The columns in both queries must have the same data types

- The columns in both queries must be in the same order in each

- Each query must select the same number of columns

UNIONby itself tells SQL to remove duplicate values in the final result;UNION ALLkeeps the duplicate valuesUNIONis a more “expensive” operation thanUNION ALLand should be used sparingly; This depends on your use case and how much data you are working with

Summary

We use both joins and unions to combine data. Joins let us combine data horizontally by adding more columns. Unions, on the other hand, let us combine data vertically by adding more rows.

Overall, there are four join types that you should know well:

-

INNER JOIN: Only keep the rows that match the constraint between the two tables -

LEFT JOIN: Keep all the rows from the left-side of the join, and only show values for the rows on the right-side that matched. Any values from the right-side that weren’t matched will be assigned anullvalue. -

RIGHT JOIN: The opposite of theLEFT JOIN- keep all the rows from the right-side of the join and only show values for the rows on the left-side that matched. Any values from the left-sie that weren’t matched will be assigned anullvalue. -

FULL OUTER JOIN: Keep all rows between both tables, but only show the values that match my constraint. All other rows that don’t match will be included, but those values will be set to null.

There are two types of UNION queries you should know:

UNION ALL: All results from tables in theUNIONare included, even if there are duplicate rowsUNION: Removes all duplicate rows from theUNIONof the tables

Now you know the theory behind unions and the most fundamental types of joins in SQL. In the practice section of 102, you will use everything you learned here and apply it to write queries to help you generate more insights for our fictional restaurant.

The join types mentioned here are the most important to know, but there are a few more join types that you may come across. There are some more advanced joins, like cross-joins, natural joins, and self-joins that you should eventually become familiar with as you enhance your skills and understanding.

Final Comprehension Check - Combining Data Using JOIN and UNION

Answer the questions below to check your understanding of what we have covered so far. Try to answer the questions first before looking at the answers:

1. What is the primary difference between joins and unions in SQL?

Click to reveal the answer

Joins combine data horizontally by adding more columns, while unions combine data vertically by adding more rows.

2. What is the key difference between INNER JOIN and LEFT JOIN?

Click to reveal the answer

`INNER JOIN` keeps only the rows that match the constraint between the two tables, while `LEFT JOIN` keeps all the rows from the left-side table and only the matching rows from the right-side table.

3. What does RIGHT JOIN do?

Click to reveal the answer

`RIGHT JOIN` is the opposite of `LEFT JOIN`. It keeps all the rows from the right-side table and only the matching rows from the left-side table. Unmatched rows from the left-side table will have `NULL` values.

4. Describe the difference between UNION ALL and UNION.

Click to reveal the answer

`UNION ALL` includes all results, even if there are duplicate rows. `UNION` removes all duplicate rows from the result set.

5. What are some advanced joins that you should eventually become familiar with?

Click to reveal the answer

Some more advanced joins include cross-joins, natural joins, and self-joins.